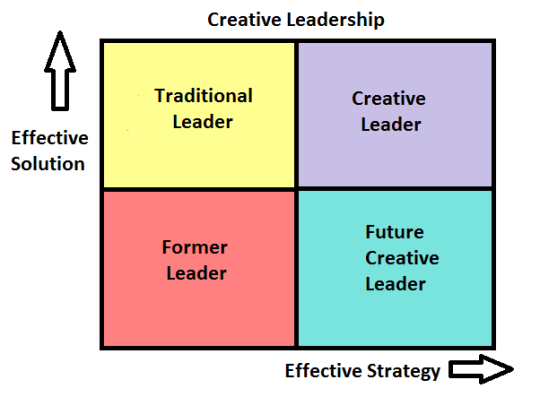

Effectiveness as a leader is dependent on a combination of personal attributes, skills, experience, and leadership style. Training in the creative-problem solving (“CPS”) method and facilitation process (referred to as “creative training”) can help leaders improve their leadership and creative thinking skills, but also gives leaders specific tools (“creativity tools”) to help them produce better decisions and outcomes. In addition, creativity training helps leaders develop a leadership style that supports creativity and the accomplishment of organizational goals. Indeed, “creativity itself has been elevated to a leadership style” (IBM, 2010, p. 26) (CEO Study). Creativity impacts nearly every aspect of leadership:

Creative leaders share a set of common characteristics that help them innovatively lead their organizations. They challenge every element of the business model to realize untapped opportunities and improve operational efficiency. Leaders grow their businesses through the exploration, selection and execution of diverse, even unconventional, ideas about the potential of new markets. They leverage new communication styles to motivate talent and reinvent relationships, both internally and across the supply chain, to create collaborative productivity. They focus on the bigger picture — the global marketplace — and how to lithely optimize the collective skills of their organizations. (IBM, 2010, p. 25) (GHRO Study)

Creative leadership has been defined as “deliberately engaging one’s imagination to define and guide a group toward a novel goal—a direction that is new for the group” (Puccio, Murdock & Mance, 2011, p. 40). Thus, the difference between leadership that is “plain vanilla” and creative leadership is that creative leadership is needed where the objective (or the path towards achieving the objective) involves some degree of novelty.

Given the importance of creativity in organizational leadership, it is somewhat puzzling why creativity is not a more common attribute in leaders. Part of this deficiency may result from the inherent difficult in “measuring” creativity. Even within the creativity field there is active debate about if and how creativity can be measured (this debate has not stopped the development of numerous so-called “creativity” tests) (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). Furthermore, creativity is seemingly intertwined with the myths of the lone investor (like Edison or Tesla), eccentric scientist (Albert Einstein), renaissance master (Leonardi Da Vinci), or modern corporate leader (Steve Jobs at Apple), who, while classified as “creative geniuses”, are discarded as outliers beyond the range of ordinary experience.

Because of these difficulties, executive training programs (i.e. MBA) have taken a results-oriented approach to creativity by offering courses in innovation, product development, and strategic planning but have neglected to teach creativity as a distinct but learnable skill. Some business schools have attempted to develop creativity in their students by immersing them in various artistic disciplines over ten-week periods (Allio & Pinard, 2005). This “immersion” approach, while having some benefits, at best represents a partial solution as even these researchers noted that “[i]mproving corporate creativity is a systematic challenge” (p. 51). The result of substantial corporate investment in innovation, innovation training, and “ad hoc” creativity training has had widely varying outcomes, but has produced few leaders that are truly creative.

Creativity training helps leaders increase their ability to set desired outcomes and wield organizational resources to achieve their objectives. Creativity training does not necessarily need to be long or complicated to be effective. According to Clapham (1997), simple creativity training focused on basic ideational skills (such as separating divergent from convergent thinking) were virtually indistinguishable from more elaborate creativity training in terms of results. A recent survey conducted by IBM on global chief human resource officers highlighted the importance of creativity training as part of leadership development initiatives:

To instill the dexterity and flexibility necessary to seize elusive opportunity, companies must move beyond traditional leadership development methods and find ways to inject within their leadership candidates not only the empirical skills necessary for effective management, but also the cognitive skills to drive creative solutions. The learning initiatives that enable this objective must be at least as creative as the leaders they seek to foster. (IBM, 2010, p. 19) (GHRO Study) (underline added)

The creative thinking skills model is an ideal model for use in creative training because it assists in the development of the distinct cognitive skills that collectively comprise creative thinking (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2011, p. 54). Current research in creativity suggests that there are seven distinct creative thinking skills (diagnostic, visionary, strategic, ideational, evaluative, contextual, and tactical thinking) (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2005, p. 62) involved in the creative process. While these seven thinking skills are improved by creativity training, these thinking skills are not unique or specific to creativity but are used in other fields including leadership (though they usually are not treated so explicitly). One way to selectively engage and improve each of the seven distinct thinking skills is by using creativity tools in a systematic manner in order to resolve a particular aspect or element of a creative challenge. Over time, the habitual use of these tools develops and strengthens the leader’s creative thinking skills from “consciously unskilled” to “consciously skilled” and eventually “unconsciously skilled” (Puccio, Murdock & Mance, 2011, p. 292). Having addressed the connection between leadership and creativity, the remainder of this paper will address how creativity training can aid in the development and use of the creative thinking skills starting with diagnostic thinking (this paper explores all but tactical thinking due to its substantial overlap with current leadership literature).

Diagnostic thinking involves “[m]aking a careful examination of a situation, describing the nature of a problem and making decisions about appropriate process steps to be taken” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2005, p. 62). Diagnostic thinking is not unique to the creativity field, but instead is practiced by most fields and professions, including leadership. Effective leadership requires diagnostic thinking—i.e., the ability to take an honest look at the “facts” as they are exist rather than as one might wish them to be. Holding facilitation sessions as a leader can be a powerful way to “collect” facts that tend to be scattered throughout an organization. As people throughout an organization have different perspectives and experiences, gathering a widely dispersed pool of participants (“resource group”) increases the chance that the “whole truth” is uncovered rather than a non-representative subset of facts.

Using facilitations to engage in diagnostic thinking is a way to promote a participatory leadership style, which in turn helps promote organizational creativity. By including people in a facilitation resource group, a leader can help the persons involved in the “problem” become part of the solution, improving both the understanding and resolution of the problem.

The involvement of the participants in the critical exploration of their own process in an intense, open, and confrontational way was an essential discovery. Results on the groups were highly effective. Significant changes were seen taking place on the spot. (Keltner, 1998, p.13).

After engaging in diagnostic thinking (and hopefully having gained an understanding of reality), leaders need to engage their capacity for visionary thinking to set the objectives and ideal destination for their organization. Visionary thinking has been defined as “conceiv[ing] of the result you want to create” (Fritz, 1989, p. 51). Visionary thinking has become more important over time as leaders cannot rely on extensive data-gathering campaigns before making decisions. In a world full of increasing complexity and rapid change, “CEOs recognize that they can no longer afford the luxury of protracted study and review before making choices” (IBM, 2010, p. 27) (CEO Study). Instead, “they are learning to respond swiftly with new ideas to address the deep changes affecting their organizations” (p. 27).

Creativity training promotes visionary thinking by developing greater capacity for imaginative thinking through the use of the affective (emotional) skill of “dreaming”—“to imagine as possible your desires and hopes” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2011, p. 140). In addition to dreaming, “storyboarding” can be an effective creativity tool that can be used to create a compelling vision. Storyboarding involves creating a series of visual depictions of the key steps, issues, or events that need to be addressed in order to eventually reach a desired outcome. The habitual use of dreaming helps make possibility-thinking a deeply-engrained mindset. A leader with a strong possibility-oriented mindset and leadership style can transform an organizational culture from one that focuses on the status quo and problems (and why things “can’t be done”) to one that believes in and actually achieves great outcomes.

Leaders with strong visionary thinking skills (i.e., imagination) are able to imagine new concepts, products, or services that others may not have considered (or thought of in a lesser sense). Strong visionary thinking skills also help leaders recognize the potential of ideas, the possibility of those ideas, and a potential path to their fruition. For example, the concept of portable consumer devices that play electronically-stored music without a CD or tape has been around for years. Yet it took the visionary leadership of Steve Jobs of Apple to imagine and create a whole new generation of portable music players (iPod, iPhone, & iPad) with accompanying docking systems and an online store. Apple, through its sleek consumer products, revolutionized the entire music industry and made obsolete clunky MP3s players and existing music distribution channels.

The essential skill that separates visionary individuals from visionary leaders is that leaders have developed the ability to communicate their vision to followers in a compelling and dynamic matter. Story telling is an effective tool that helps leaders “to create a vision of the future, a coherent sense of the past and a journey for the listener. In effect, [stories] take the listener from the past, to the present, and on to the future” (Hansen & Parry, 2007, p. 284). Telling stories is a useful tool to promote visionary thinking and leadership as:

[Stories] provide an appreciation of the possibilities that the future might offer to followers. Put another way, they articulate scenarios that are possible for the future…. [T]hey make sense of and communicate a future that the organization can determine and pursue for itself. That future is bounded by many barriers, but within that bounded rationality, visionary leaders confirm confidently that the organization can hew out its own future (p. 286).

Over time, the use of dreaming, storyboarding, storytelling, and other creativity tools designed to promote visionary thinking helps leaders develop both a compelling vision and the ability to communicate the vision to followers in a manner that resonates. However, once leaders have firmly set the vision and communicated it to their organization, they need to engage in strategic thinking to close the gaps between the vision and current state.

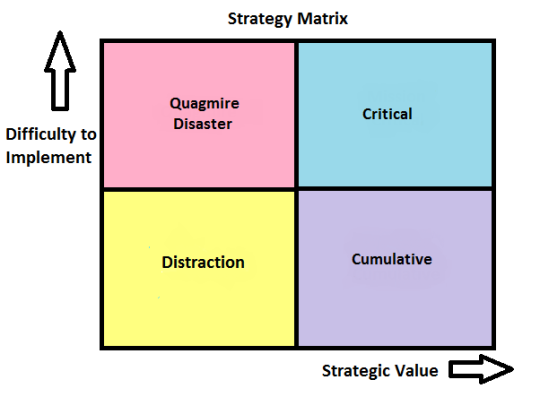

Strategic thinking involves “identifying the critical issues that must be addressed and pathways needed to move towards the desired future” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2005, p. 62). Almost all leaders (one would hope) engage in some form of strategic thinking usually as part of an annual or periodic strategic planning process. Creative leaders, however, are more likely to engage in strategic thinking as an ongoing and iterative process rather than a once-a-year, formal event:

Standout CEOs expressed little fear of re-examining their own creations or proven strategic approaches. In fact, 74 percent of them took an iterative approach to strategy, compared to 64 percent of other CEOs. Standouts rely more on continuously re-conceiving their strategy versus an approach based on formal, annual planning (IBM, 2010, p. 26) (CEO Study).

Besides engaging in strategic thinking more often, creative leaders approach strategic thinking with greater “openness” and stronger commitment to a complete and comprehensive strategic process. A leader without creative training might start a strategic planning session with only a few challenge question(s) (such as “how can we increase revenue by X% next year”) without much consideration of alternative challenge statements, and then start into the ideation phase by developing a list of possible strategies and courses of action. In contrast, a leader trained in CPS would realize the strategic phase of CPS involves both divergent and convergent thinking and push his or her team to generate twenty or thirty (or more) challenge statements ranging from “how might we acquire more market share” to “how might we acquire our biggest competitor” to everything else in between. Thus, only after careful convergence on the best challenge statement(s) would a creative leader launch into the ideation phase of CPS. After all, working on the “right” problem is essential to a successful ideation phase as “[t]he more clearly the challenge is stated, more likely you to get the kind of ideas that can be used to solve the problem” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2011, p. 175).

Ideational thinking has been defined as “producing original mental images and thoughts that respond to important challenges” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2011, p. 171). Ideational thinking is the process of generating numerous ideas that each might potentially resolve (or reduce) the gap between the vision and current state. While there has been much written about the “eureka” moment in which a brilliant idea is born, more often than not the new idea comes only after hours of tedious labor of ideational “grunt work” and an often prolonged incubation period. As a result, it is often said that “innovation is 5% inspiration and 95% perspiration” (Birkinshaw, Bouquet & Barsoux, 2011, p. 44).

Creative leaders can encourage organizational participation in creativity and idea generation by using brainstorming, forced connections, or similar ideational techniques. When conducting a brainstorming session, a facilitator with a participatory leadership style (characterized by involving others) as compared to a supervisory style (characterized by directing others) tends to promote increased ideation as a group (Anderson & Fiedler, 1964). In addition, leaders need to ensure that brainstorming sessions are conducted effectively to get the maximum output from ideational efforts. For instance, one study found that brainstorming produced more ideas when conducted individually (results aggregated together) than when conducted in groups, possibly because of social inhibition (Lamm & Trommsdorff, 1973). A possible implication from this study is that when group brainstorming is conducted, efforts need to be taken to put the members of the resource group at ease to promote maximal ideational production.

In order to support and promote idea generation throughout an organization, creative leaders should adopt a leadership style that creates a climate that is conducive to creativity. One important practice as a leader is to encourage ideas thus “increasing the likelihood that followers will bring ideas forward in the future” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2011, p. 171). Other important behaviors displayed by creative leaders in order to develop a creative climate include openness to change, involving followers in problem solving efforts, responding positively to new ideas, encourage debate, entertaining diverse perspectives, encouraging freedom and autonomy, encouraging risk taking, and accepting mistakes (p. 271-72).

A common misconception about creative thinking is that it undisciplined thinking, resulting in novel ideas that, if pursued, can sometimes represent a colossal waste of time and organizational resources. Convergent thinking is an essential skill because “the problem for most large organizations usually isn’t a shortage of ideas. The real challenge is figuring out how to ferret out the good ones” (Reitzig, 2011, p. 47). This is especially true in large organizations that generate thousands of ideas, but then have to incur real costs in deciding which ideas to implement and how to implement them. Leaders should ensure that their organizations have an effective process for evaluating the ideas resulting from ideational efforts and developing the best ideas further. While convergent thinking is used at every step of CPS, it is most prevalent in evaluative thinking, which usually follows immediately after the ideation phase of CPS.

Evaluative thinking has been defined as “[a]sessing the reasonableness and quality of ideas in order to develop workable solutions” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2005, p. 62) and includes both divergent and convergent thinking. There are several principles that are essential to successful evaluative thinking. In contrast to critical judgment, “affirmative judgment” examines what is “right” about an idea (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2011, p. 96-97). In addition, as ideas are often conceived in a partially formed state, “transforming” an idea means “changing rough ideas into more elaborated and workable solutions” (p.193). Because even good ideas have weaknesses, it is important to “strengthen” ideas by “focusing first on the positive aspects of an idea and then by seeking ways to overcome shortcomings associated with the idea” (p. 193). The creativity tools of POINt (positive, opportunity, issues, new thinking) and PPCo (pluses, potential, concerns, opportunities) are useful because they combine affirmative judgment, divergent and convergent thinking into a single creativity tool focused on evaluating, transforming, and strengthening ideas (p. 193).

Evaluative thinking is an absolutely critical leadership skill, especially when evaluating novel ideas for possible implementation. “It is possible for [divergent thinking] to be accepted without exploration (i.e., divergent thinking without convergent thinking). If such novelty proves to be ineffective, we can speak of ‘recklessness,’ which raises the danger of disastrous change” (Cropley, 2006, p. 399). Ineffective evaluative thinking can potentially result in the rejection of an otherwise effective novel idea (a false negative) or the positive evaluation of an ineffective novel idea (false positive) (p. 400). When conducted effectively, however, evaluative thinking can identify a potentially valuable idea, and carefully elaborate and support its growth into a fully developed solution that leads to significant positive change when implemented. Because of the potential for prematurely discarding good ideas or implementing bad ideas, evaluative thinking needs to be conducted carefully and in a systematic fashion. However, even after an idea has been fully developed, it may need to be modified in order to gain acceptance in a particular environment or context.

Contextual thinking has been defined as “[u]nderstanding the interrelated conditions and circumstances that will support or hinder success” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2005, p. 62). Contextual thinking is a valuable leadership skill because “[t]o successfully introduce novel solutions or to bring about creative change, leaders must learn to skillfully work within their social contexts” (Puccio, Murdock, & Mance, 2011, p. 208). A “stakeholder analysis” is a useful creativity tool for deploying contextual thinking in a given situation. This tool is used to rate stakeholders from supportive to opposing (and everything in between), and gives the user the opportunity for divergent thinking as to how to modify the solution or persuade vital stakeholders to move to a supportive or at least a non-opposing position (p. 213). By employing contextual thinking (through a stakeholder analysis or similar creativity tools), a creative leader can build internal or external consensus concerning a novel solution and secure its successful adoption and implementation.

In summary, creative thinking and facilitation training can greatly improve leadership skills. Creative leaders are skilled at developing organizational vision, defining the “right” problem, and generating large number of ideas. In addition, creative leaders are able to recognize good ideas and turn them into solutions and gain acceptance of their proposed solutions from decision makers and constituencies. Further, creative leaders are more likely to promote organizational cultures where creativity thrives, employees are actively fully engaged, and challenges are overcome using CPS. Companies can realize significant gains in terms of leadership development and actual results by developing the creative thinking skills of leaders through CPS and facilitation training.

Personal Reactions to Research

After reading the research, I have concluded that the CPS thinking skills model and facilitation training offers a robust framework that can be overlaid on current literature and research on leadership. Current leadership writing lacks a theoretical framework to address creativity that can be supplied by CPS, particularly the seven thinking skills that comprise the creative thinking skills model. From research, it appears that the business world usually engages in processes that resemble CPS but apply creative thinking haphazardly and less thoroughly than with CPS. I am interested in reviewing additional research regarding the connection between facilitation, leadership styles, and creative climate within an organization. It seems that a leader that is willing to promote CPS and facilitations throughout an organization would usually tend to have a participatory leadership style (or be willing to develop one). Further, CPS and facilitations (assuming they taken seriously) would also tend to promote a creative climate within an organization, which in turn would make leaders more effective.

From reviewing publications such as the IBM CEO study (2010), it is clear that business world recognizes the need for creative leadership. It is equally clear, however, that business schools and commentaries lack training and experience in the creativity fields, and as a result, have resorted to “ad hoc” training methods in creativity. While describing the positive impact of immersing students in artistic mediums, Allio and Pinard noted that “[i]mproving corporate creativity is a systematic challenge” (2005, p. 51). CPS and facilitation training could fill the need for creativity training that is currently missing in business world and leadership literature. How might we take CPSM and facilitation training into the business world and education?

References

Allio, R. & Pinard, M. (2005). Innovations in the classroom: Improving the creativity of MBA Students. Strategy & Leadership, 33, 49-51.

Anderson, L. & Fiedler, F. (1964). The effect of participatory and supervisory leadership on creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 48(4), 227-236.

Birkinshaw, J., Bouquet, C. & Barsoux, J. (2011). The 5 Myths of Innovation, MIT Sloan Review, 52(2), 42-51.

Clapham, M. (1997). Ideational Skills Training: A Key Element in Creativity Training Programs. Creativity Research Journal, 10(1), 33-44.

Cropley, A. (2006). In praise of convergent thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 18(3), 391-404.

Fritz, R. (1989). The Path of Least Resistance: Learning to become the creative force in your life. New York: Fawcett-Columbine.

IBM (2010). Capitalizing on Complexity: Insights from the Global Chief Executive Study. Retrieved from http://www.ibm.com (CEO Study)

IBM (2010). Working beyond Borders: Insights from the Global Chief Human Resources Officer Study. Retrieved from http://www.ibm.com (GHRO Study)

Hansen, H. & Parry, K. (2007). The organizational story as leadership. Leadership, 3(3), 281-300.

Keltner, J. (1989). Facilitation. Management Communication Quarterly, 3(1), 8-32.

Lamm, H. & Trommsdorff, G. (1973). Group versus individual performance on tasks requiring ideational proficiency (brainstorming): A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3(4), 361-388.

Puccio, G., Murdock, M., & Mance, M. (2005). Current developments in creative problem solving for organizations: A focus on thinking skills and styles. Korean Journal of Thinking & Problem Solving, 15, 43-76.

Puccio, G., Murdock, M., & Mance, M. (2011). Creative Leadership: Skills that drive change. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Reitzig, M. (2011). Is your company choosing the best innovation ideas? MIT Sloan Management Review, 52(4), 47-52.

Sternberg, R. & Lubart, I. (1999). The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms. In R. Strenberg (Ed.), Handbook of Creativity (pp. 3-31). Cambridge University Press: New York.